Less is More

But simple isn't easy

Coming to you from: PlantShed Cafe, East Village

How face masks fooled Bengal tigers

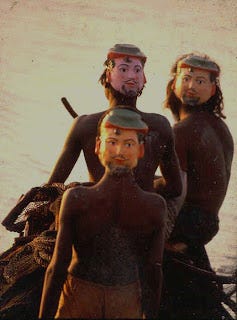

In the Sundarbans region of India and Bangladesh from 1947-1983, around 50 people died each year from tiger attacks. Local villagers and fishermen lamented that the tigers are so stealthy that “if you see one, it will only be as its jaws clamp down on your neck.” Villagers built fences, only went out in groups, and even crafted straw men with electric wires. Nothing helped.

Finally, someone made a simple observation that changed the locals’ lives: Bengal tigers attack from behind. They started wearing human face masks on the back of their heads to fool the tigers and immediately saw a drop in attacks. In fact, the only ones that died from attacks were ones that took their masks off to eat lunch. Sounds almost too simple, but it worked astoundingly well.

Complex problems often don’t require complex solutions - simple is powerful.

Source: Vinod Rishi

History’s best teacher

Richard Feynman, arguably the most influential modern physicist, was known for his ability to break down the most complex problems into simple, jargon-less axioms. He won a Nobel Prize, revolutionized our understanding of quantum electrodynamics, helped develop the nuclear bomb in the Manhattan Project, and even cracked safes.

Yet, despite these accomplishments, one of the most difficult tasks he was assigned was teaching physics to freshmen at Caltech. The university wanted all students to have the same foundation in physics; who better to teach first principles than the man who famously explained precalculus in just a page, starting from how to count on a number line? He created a lecture series that explained concepts to 18-year-olds with fundamentals that did not rely on any prior knowledge. This series was so powerful that PhDs, professors, and even guests sat in on his classes.

One day, a Caltech professor asked Feynman to explain why half-spin particles obey Fermi-Dirac statistics, to which Feynman said “I’ll prepare a freshman lecture on it.” A few days later, he said, “I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t reduce it to a freshman level. That means we don’t really understand it.”

One thing is clear: elementary does not mean easy. Even science’s finest acknowledged this.

"If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter."

- Blaise Pascal (The Provincial Letters, 1657)Occam’s Razor

Imagine you’re buying something at the gas station that will cost at most 99 cents. You have small pockets, so you want to hold only the absolute minimum number of coins needed to pay for the item with exact change, regardless of how much it costs. What is the fewest number of coins you can carry that allows you to produce any exact amount up to 99 cents? (Scroll to the bottom for the solution).

We are often best off when we have just enough to tackle any problem. Any more and we are holding extraneous information; any less would mean we are not adequately prepared for all outcomes. We really have to cut it close to keep it just simple enough.

Enter Occam’s Razor, a principle that suggests the simplest explanation is often the best one. Thanks to William of Occam, a Franciscan friar who studied logic in the 14th century, we know that “plurality should not be posited without necessity.” If two models are equal in their explanatory power, then we should resort to the one with fewer assumptions because it avoids unnecessary complexity.

For example, let's consider two statements:

The sidewalk is wet because it rained.

The sidewalk is wet because there was a water balloon fight.

The second statement requires more assumptions, while the first is more feasible and commonplace. The gap between these two is obvious and has little impact on our lives, so let’s look at another example closer to home:

My interviewer has not contacted me.

My interviewer has not contacted me because my interview went poorly.

At first glance, it doesn’t seem like we are making any major assumptions about the interviewer. However, we are now introducing the interviewer’s thoughts into the observation, which are unknown. This tendency to overthink and make assumptions is innately etched into our internal dialogues. As always, we are works-in-progress and have the ability to learn how to apply Occam’s Razor. Once trained, you will be conditioned to deal with ground truths, not offshoots.

Ways to simplify your life:

Be aware of complexity bias: Farnam Street summarizes this bias eloquently:

“Marketers make frequent use of complexity bias. They do this by incorporating confusing language or insignificant details into product packaging... Most people who buy ‘ammonia-free’ hair dye, or a face cream which ‘contains peptides,’ don't fully understand the claims. Terms like these often mean very little, but we see them and imagine that they signify a product that’s superior to alternatives.” Do you really need your bag of baby carrots to be labeled vegan?When in doubt, zero it out: Got constant back-to-backs meetings and weekly check-ins? Your first instinct might be that a regular cadence of meetings helps your team stay organized, but this is at the cost of a cluttered schedule. Even if the meeting isn’t necessary, you join your Zoom meeting, exchange pleasantries, and then state “nothing to discuss on my end this week!” before leaving the call and repeating thrice more. Ditch this system and clear your schedule. Treat meetings as “unnecessary until proven necessary” and treat your time like gold. Schedule syncs on an ad-hoc basis and find more efficient ways to stay on track. The world’s best ideas started with a blank canvas.

Reframe your problems: Consider the following example that a hotel is dealing with: Three contractors were hired to fix the slow elevator in the hotel lobby. The first contractor says, “I can do it for $30k, I’ll install a new, faster elevator.” The second responds, “I can do it for 3k, I’ll replace the current elevator’s motor with a faster one.” The last one responds, “I can do it for $300, I’ll add a mirror inside the elevator.”

Contractor 3 (he won the mandate but still upcharged the hotel) reframed the problem from “the elevator is slow” to “the wait feels long.” Simple solutions manifest when you think about the problem differently, so don’t be scared to question the question.

Source: Harvard Business Review

As you bring these methods into your life, remember that some things are too complex to reduce. Additionally, don’t let the pursuit of simplicity stymie the natural trial and error process that comes with being human, so don’t be fearful of hypothesizing and experimenting when appropriate. Leaps of faith are still part of making progress, whether you’re in the villages of coastal India or the lecture halls of Caltech. Stick to first principles, keep your eyes peeled for assumptions, and be ready to wipe the slate clean when there’s clutter.