History looks backwards, you shouldn't

The perils of outcome bias

Coming to you from: Ripple Cafe (MIT)

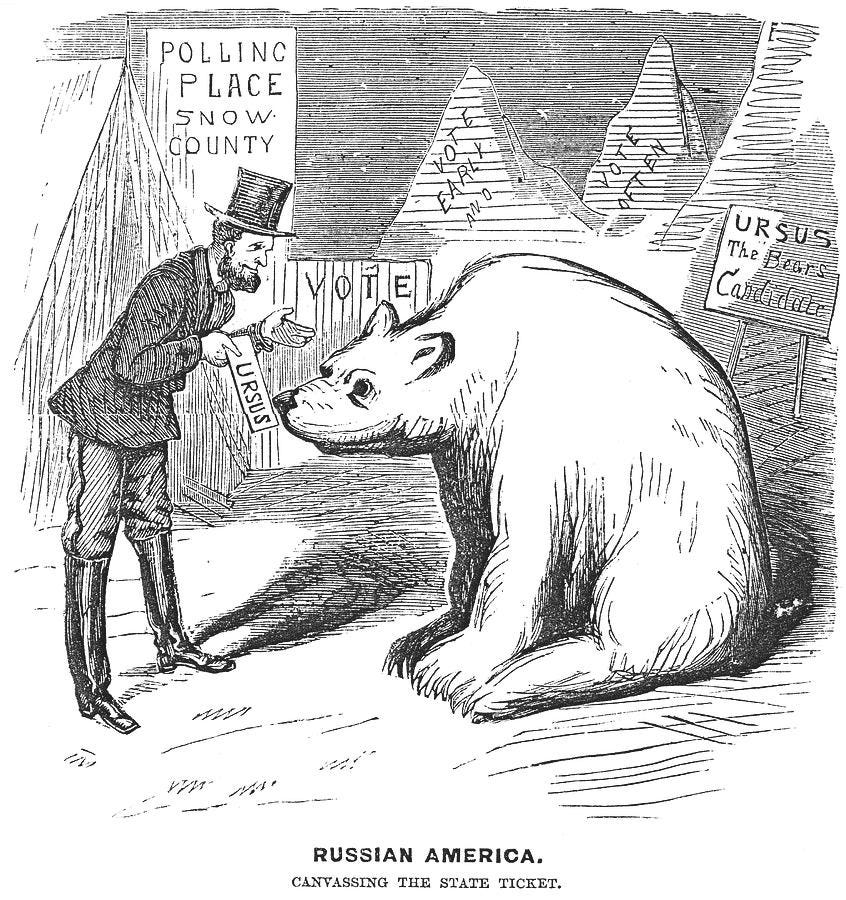

Seward’s Folly

When the U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward signed a treaty with Russia to purchase Alaska for $7.2 million, he was ridiculed. Congress was ruthless, calling Alaska a “polar bear garden” and “Seward’s icebox.” Seward had always been a staunch proponent of territorial expansion and believed 2 cents per acre was too good of a deal to pass up, even if it meant just acquiring some extra backyard space (one that is 20% as large as the contiguous 48 states). In Seward’s lifetime, everyone considered his Alaskan purchase to be nothing but an overpriced Russian ice sculpture garden. That is, until he was posthumously vindicated.

Over 25 years after Seward’s death, a certain yellow ore was found underneath the polar bear garden. The discovery of gold in 1898 drew people from all over the States, leading to even more resource discoveries. Today, oil and gas production from Alaska’s federal land alone generates $52 billion in revenue…per year.

Seward might still be known in history as a frivolous spender had gold or resources not been discovered in Alaska. Instead, he inadvertently purchased a territory that is a global leader in natural resource production 150 years later. The quality of his decision and the outcome of his decision were not causally linked. It’s only after knowing the result that history considers the Alaskan Purchase a winning deal.

Source: Granger Historical Archive; a politician trying to find voters in newly acquired but uninhabited Alaska (1867)

Blockbuster and Netflix

History is rife with outcome bias, and it isn’t confined to politics or conquests.

Today, people widely believe that Blockbuster signed its own death warrant when it declined the opportunity to purchase Netflix for $50 million in 2000. The narrative conveniently cuts out a few important details:

Netflix was not profitable, nor was it close to profitable (net loss of $58 million in 2000)

$50 million was an objectively high valuation at the time for any company, especially for a company selling DVDs by mail

The dot-com crash had set the stage for a grim outlook for the broader economy, with technology companies being chastened doubly

Netflix went to Blockbuster for a lifeline out of desperation, not from a place of power; the Netflix founders visited the Blockbuster HQ multiple times for a chance at surviving the tough economic conditions

Is it fair to say that John Antioco, CEO of Blockbuster, made an uninformed and short-sighted decision? Had he accepted the deal and paid eight figures to two founders who were losing money shipping DVDs in the mail, we might have called the deal Antioco’s Folly or the DVD garden. Alternatively, if Netflix didn’t become as successful as it is, we may have deemed Antioco prudent (unlike that one cousin we all have that still keeps buying NFTs).

Whether someone is acquiring an icy territory or a DVD business, we often unfairly judge the merits of a decision by its outcome.

Source: OpenAI’s DALL-E 3 (Prompt: “Netflix vs. Blockbuster rivalry in Super Mario 8-bit aesthetic”)

Outcome bias is rampant and dangerous

The contrasting legacies of Seward and Antioco underscore that we have a backwards view of success and failure. If you consider yourself, like many high achievers, to be “results-driven,” you are at further risk of this bias. Few outsized outcomes are replicable, yet we are inclined to only reuse what has worked for us.

Outcome bias comes at the dangerous cost of critical thinking. The more you have an idea of what has worked for you, the more likely you are to form heuristics. By definition, heuristics are mental shortcuts (read: cutting corners to reduce thinking). When we’re in a hurry, they’re great. But when you tell others to do things a certain way because that way worked for you, you’re taking a shortcut at their expense by inhibiting their critical thinking.

This bias is everywhere. Parents limit the scope of their children’s area of study to fields they have seen produce jobs in the past. Investors bet millions of dollars and then use the results to retroactively justify their skill or blame the market (information asymmetry). Ultimately, outcomes can be a result of many factors outside of our control, far outside the realm of just the quality of the decision itself. We shouldn’t be quick to infer direct causality in our lives.

What you can do about it

The human mind loves cause and effect - we’d go crazy if we couldn’t ascribe patterns to things that happen around us. Naturally, we are prone to set fixed goals and orchestrate our actions accordingly. In practice, there’s no guarantee these plans work, but biology predisposes us to outcome biases.

The good news is that there is a simple (not easy) fix for this bias. The bad news is that it requires proactively rewiring our psyches.

Don’t chase outcomes: Let your actions be dictated by sound judgment and the facts in the present, not in pursuit of fixed outcomes. Not to wax mathematical, but if A represents our actions and B represents the outcomes, life fits squarely into none of the below function types (as an exercise, try coming up with examples that fit squarely into either general or surjective). Life isn’t a replicable set of domains and ranges. Any A can result in many Bs, and many As can lead to the same B. And lastly, remember that we don’t look at Bs to backsolve for As.

Source: mathisfun.com (no, I don’t own this domain)

Truly internalize that mistakes aren’t bad: We instinctively aggrandize outcomes because we are fearful of bad ones. If we learned to see mistakes as opportunities, we’d focus much more on intentions and the journey. And if you need help remembering that mistakes are unfairly blown out of proportion, remember that humans are also guilty of survivorship bias - we view mistakes as fatal because successful stories only face non-fatal ones.

Regularly remind yourself of this bias: Michael Singer’s Living Untethered: Beyond the Human Predicament postulates that we are not our thoughts, but rather observers of both life and our thoughts. Adopting this mindset makes it easier to view biases as lenses that tint our view of the world. Simply knowing the lenses are there can be a very powerful reminder of the distortions and corrections our biases introduce into our observation of the world and our thoughts. In this case, writing down your initial intentions is a great way to start. It’ll help you clarify when causality is actually there and when it merely appears there.

Be wary of outcome bias. Live your life with deliberate care for intentions instead of results and you will witness a paradigm shift in the quality of your judgment and decision-making.